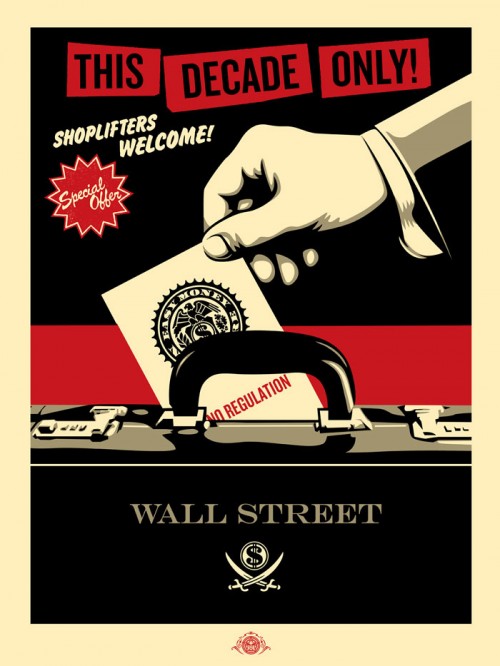

Wall Street Reform & Campaign Finance Reform Issues Still Loom

I know these issues might not be exciting to ponder, but Wall Street reform and campaign finance reform are inter-related and crucial in terms of fighting the greed of the powerful and restoring basic fairness in our society. It is very worth reading the article below. Thanks for caring.

-Shepard

Citigroup’s $7 Billion Fraud Deal: The Clique’s Still Clicking in D.C.

Citigroup’s $7 Billion Fraud Deal: The Clique’s Still Clicking in D.C.

by Richard (RJ) Eskow

Pop quiz: Which bank is widely considered too big to fail, needed (and got) a $45 billion government loan during the financial crisis, recently failed a stress test performed by the Federal Reserve — and has enjoyed a revolving-door relationship with both the Clinton and Obama administrations?

If you answered Citigroup, congratulations.

Citigroup is back in the headlines as the result of a new settlement with the Justice Department over its mortgage fraud, reportedly for the sum of $7 billion. This deal is being trumpeted as a major win for the American people. It’s not. The money’s not enough (and some of it probably won’t be paid out), the wrong people are paying, and there will be no prosecutions for criminal behavior.

From a moral perspective, the lack of prosecutions is probably the most troubling aspect of this deal, and it keeps happening. Somehow the Justice Department is able to reach one billion-dollar settlement after another to resolve charges of massive criminality without indicting a single criminal.

With the continued dominance of what Sen. Elizabeth Warren has called the “Citigroup clique” in Washington, there’s no question that the old adage is still true: It pays to have friends. But where did this bumbling behemoth come from in the first place?

A defendant is born

The merger between Citibank and Travelers was illegal when it was first announced in 1998. But the parties were confident that both the Republicans in Congress and the Democrats in the Clinton White House would come through for them, so they announced it anyway. As Travelers CEO Sandy Weill said at the time, “we have had enough discussions to believe this will not be a problem.”

It wasn’t.

Citi’s friends at the time included Republican Sen. Phil Gramm and Democratic Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin. The Federal Reserve gave the new institution a temporary waiver, reportedly with Rubin’s blessing. Then the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act repealed Glass-Steagall and other legislation which forbade mergers of this type, on the eminently reasonable grounds that the institutions they might create would be too big to fail.

The law passed Congress and a bipartisan landslide, with 205 Republicans voting for it in only 16 against. Among Democrats the “yes” margin was 138 to 69. Bill Clinton signed the law on November 12, 1999, declaring that “financial services firms will be authorized to conduct a wide range of financial activities, allowing them freedom to innovate in the new economy.”

Added President Clinton, “Removal of barriers to competition will enhance the stability of our financial services system.” (Clinton made headlines recently when he attempted, against historical evidence, to defend his record on this issue.)

The net result? Gramm got rich and Rubin got richer — as a senior executive and later as CEO in the newly created Citigroup. (President Clinton did pretty well for himself, too.) The rest of the country didn’t make out so well: homeowners and investors were massively defrauded by Citigroup, the economy was shattered by it and other too big to fail banks, Citi required and received a $45 billion emergency loan on Rubin’s watch, and the rest of us are still paying the price for Wall Street’s actions — in lost wages, lost wealth, and lost jobs.

A fragile behemoth…

This is how the fragile behemoth known as Citigroup was born.

There are compelling public policy reasons why too big to fail banks should be broken up. In Citigroup’s case, there are increasing signs that this specific bank has become unmanageable. First, there’s the matter of that Fed stress test. Citi is the only top-five bank to fail this test, and it has now flunked it for the third time in two years. Five years after the financial crisis, when Citi performed so badly under CEO Robert Rubin, the Fed says it’s still concerned about “”overall reliability of Citigroup’s capital planning process.”

As a financial analyst told the New York Times Dealbook page, “it’s not as though haven’t had time to clean up their act.”

Citigroup also continues to carry risk related to Argentinian debt, and Mexican government authorities issued arrest warrants for former executives of a Citigroup subsidiary there in a $400 million fraud case. These problems have led some observers to conclude that the bank is simply too large, too diverse, and to dispersed geographically to be managed effectively.

And there’s no question that that Citigroup has become “too big to fail,” posing a systemic threat to the economy while at the same time enjoying the implicit government guarantees — and therefore the unfair market advantage — which size brings. (A recent study confirmed the existence of this advantage.)

And if that market advantage is quantifiable for all too big to fail banks, imagine how much greater it is for one which enjoys such a cozy relationship with the Executive Branch.

… with friends in high places

Sen. Elizabeth Warren drew a great deal of attention (and some cheers) when she wrote an editorial about the existence of a “Citigroup clique” which took shape during Bill Clinton’s presidency, escaped accountability for its role in the 2008 crisis, and hold sway in the Obama White House.

As Sen. Warren noted, Federal Reserve vice chair StanleyFischer was merely the latest ex-Citigroup appointee to come out of the Obama Oval Office. Warren notes that

“…three of the last four Treasury secretaries under Democratic presidents have had Citigroup affiliations before or after their Treasury service. (The fourth was offered, but declined, Citigroup’s CEO position.) Directors of the National Economic Council and Office of Management and Budget, as well as our current U.S. trade representative, also have had strong ties to Citigroup.”

That trade representative, Michael Froman, received more than $4 million in bonuses from Citigroup, just as he was leaving to negotiate vital international treaties that will affect the bank’s bottom line.

The revolving door swings the other way, too. Peter Orszag, President Obama’s former director of the Office of Management and the Budget, left government service to become a senior executive at Citigroup.

A sordid record

Its close association with two successive Democratic Administrations has not conferred upon Citigroup an excessive respect for the law, to put it mildly. In fact, Citigroup’s record isn’t pretty. It includes:

the Mexican banking incident for which warrants were recently issued;

a class action lawsuit filed after it illegally raised rates for credit card customers;

slap-on-the-wrist fines for lying to investors about40 billion in subprime exposures;

propping up WorldCom stocks in return for enormous fees, which led to a2.65 billion fine;

650,000 in fines for disclosure and supervisory violations relating to Citi’s Direct Borrow Program and 1.5 million for supervisory violations relating to a broker who misappropriated over60 million from cemetery trust funds (citations from corp-research.org);

a 285 million fine from the SEC for defrauding investors in a1 billion housing-related CDO;

a590 million settlement for misleading investors in the banks’ own stock (Rubin was a named defendant in that lawsuit);

another 730 million settlement for deceiving bond and preferred-stock investors;

and now Citigroup faces a lawsuit over discriminatory lending in Los Angeles, after allegedly targeting minority borrowers for predatory loans.

(We’re leaving out quite a few cases because space is limited and there were so many misdeeds. More of them can be found here.)

Another day, another deal

All that sounds bad — and it is. But, you may be thinking, at least this latest settlement restores some semblance of justice toward Citigroup. After all, $7 billion is a lot of money, isn’t it?

One answer to that question is, Not compared to the $10 billion which was originally reported as the government’s settlement demand. (There’s always the possibility it may have a pre-arranged public ritual; government asks for $10 billion, the bank offers $4, and they split the difference. But, even if that’s not the case, that suggests a negotiation between parties of equal leverage and power. Is that what we have here?)

The $7 billion sum is also smaller than it appears when a large but unspecified percentage of it is to be given in the form of “consumer relief,” rather than in hard dollars. Big banks have been notoriously deceptive in the way they calculate these figures. They have counted debt renegotiations that work in their favor against these sums, along with renegotiations which apply to debts held by others

Let’s put it this way: accepting these stated dollar amounts as real requires an enormous amount of trust in the very institutions which committed fraud in the first place.

What’s more, Citigroup has been one of the worst actors in a very undistinguished crowd. As the New York Times reported in 2008, it was especially aggressive in profiting of risky business. “I just think senior managers got addicted to the revenues and arrogant about the risks they were running,” said one in its CDO group. “As long as you could grow revenues, you could keep your bonus growing.”

Then there’s the aforementioned absence of indictments. No criminal bankers will be held accountable for their crimes. That means they have no reason not to keep committing them. Most settlements, including this one, don’t even require individual bankers to forfeit income they earned through illegal action.

Who pays?

Who’ll pay the tab for this settlement? The same investors who were defrauded in the case which led to a $590 million settlement — the case which named Rubin as a defendant.

In other words, the defrauded will be picking up the tab for the very bankers who defrauded them — that is, unless they were smart enough to dump their Citigroup stock after the last settlement.

Machinery of fraud

A Citigroup subsidiary was one of the co-owners and frequent users of MERS. That’s the database and false-front corporation which played such a key role in the crisis. MERS facilitated the packaging, bundling, and slicing up of mortgages which drove the housing bubble. Later it proved especially useful in enabling banks commit widespread foreclosure fraud, after the bubble burst and the American people were left holding the tab.

(We obtained a number of MERSCorp internal documents, which we reported on and analyzed here.)

As Yves Smith notes, MERS recently had two high-profile legal setbacks, although neither were the result of initiatives by the Holder/Obama Justice Department.

The Justice Department could demand a dramatic change in MERS practices, or even its dismantling, as part of the settlements it negotiates. Instead it has chosen to leave the machinery of fraud in place, even as the structure of its financial settlements (and its lack of prosecutions) ensures that the incentives to commit fraud remain as strong as ever.

One-clique purchasing

That doesn’t necessarily mean there has been an explicit quid-pro-quo. When government officials are so closely tied to the Wall Street clique in general — and the “Citigroup clique” in particular — that’s neither likely, desirable, nor necessary. Most bankers and government officials would probably be offended by the very idea, regardless of the chair they happen to occupy the moment.

But the people who would be indicted or fined are, more often than not, people that have been the clients of Wall Street attorneys like Eric Holder. They are the future (and now current) clients of revolving-door Justice Department officials like Lanny Breuer. And they’re the people who raise money for elections, including presidential elections.

They are, in short, “people we know.”

It goes back into something we’ve called the “147 people” phenomenon. Most people can only know, really know, about that many other human beings. Those people form an individual’s social group, and it becomes unthinkable to ostracize them — much less to indict them or hold them personally responsible for criminal behavior.

What’s more, the revolving-door offers government officials an irresistible temptation — one they’re probably reluctant to acknowledge. Why break up the bank which might have enriched you in the past, or is likely to do so in the very near future?

And so these deals keep getting made, while the big banks keep getting bigger. Not everybody involved in this story thinks that’s a good idea, Sandy Weill, for example, has suggested that banks like Citigroup should be broken up. But then, Weill is retired. He’s not working on Wall Street or in government.

In other words he’s not part of the clique.

But, even though he’s officially retired, Robert Rubin is still a member in good standing. He met with Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner a number of times after the financial crisis, for example, even as he and his institution were the targets of investigation.

That’s how too big to fail banks stay big. It’s how their bankers avoid prosecution. And it’s how good government goes astray, sometimes taking entire economies with them as they go.